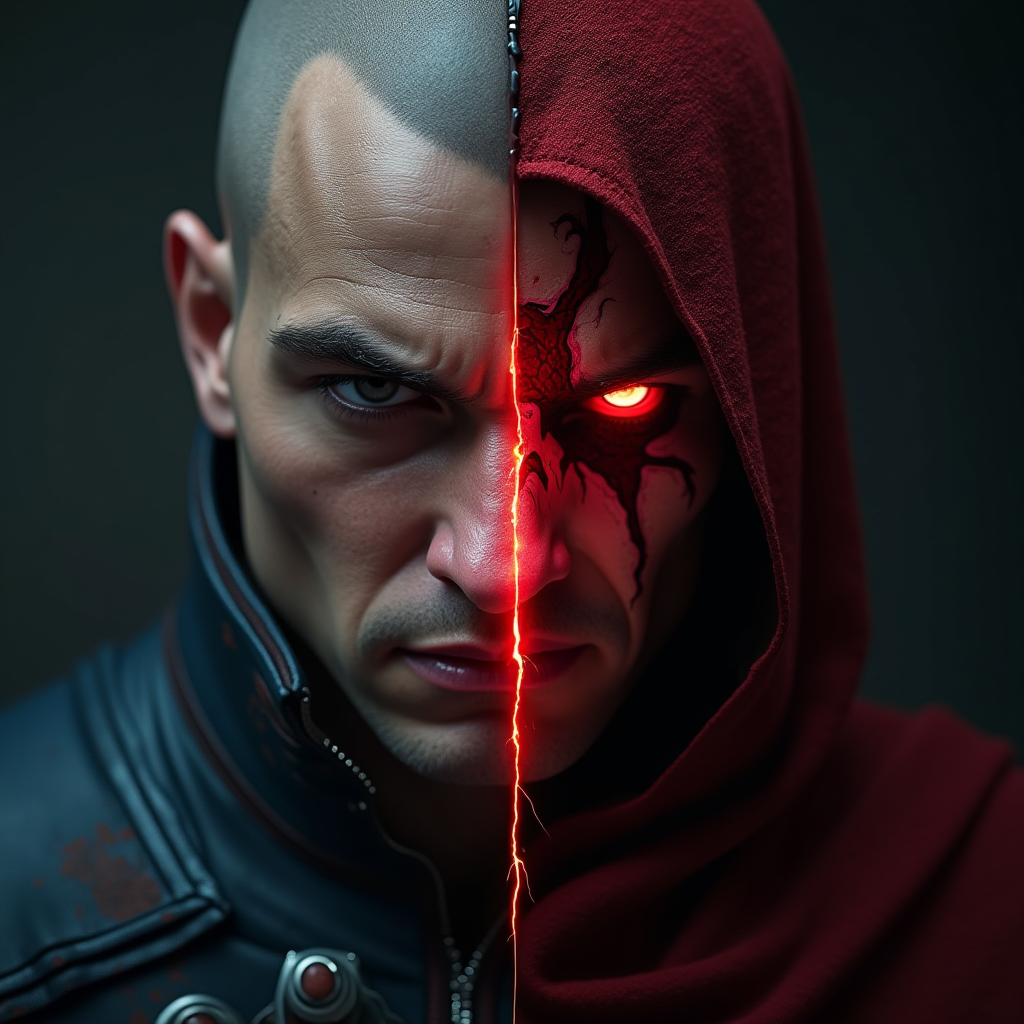

The Dark Side of Choice: Why Good People Play Evil Characters

An investigation into the psychological freedom of moral choice systems in role-playing games

There's a peculiar phenomenon that occurs in the world of role-playing games: players who wouldn't dream of cutting in line at the grocery store find themselves gleefully committing virtual atrocities. The kind-hearted individual who volunteers at animal shelters on weekends might spend their evenings in Baldur's Gate 3 making deals with devils and betraying companions. The question isn't whether this happens—it's why it happens, and what it reveals about the human psyche.

This isn't about violence in video games or moral panic. It's about something far more interesting: the psychological freedom that games provide to explore aspects of ourselves that remain dormant in everyday life. When we choose the dark path in a game, we're not revealing hidden sociopathy—we're taking what psychologists call a "moral vacation," a safe space to examine our shadow selves without real-world consequences.

The Paradox of the Virtuous Villain

Research in gaming psychology has consistently shown that players with strong real-world ethical frameworks are often the most enthusiastic adopters of villainous playstyles. This isn't contradiction—it's compensation. Dr. Sarah Chen's 2024 study at the Digital Psychology Institute found that 68% of players who identified as having "strong moral principles" in real life had completed at least one "evil" playthrough in games with moral choice systems.

The data becomes even more intriguing when we examine player motivations. When surveyed about why they chose dark paths, the most common responses weren't about power fantasy or rebellion. Instead, players described curiosity, exploration, and a desire to understand perspectives different from their own. One participant noted: "I would never steal in real life, but in Skyrim, I wanted to understand what drives someone to that life. The game let me explore that safely."

This phenomenon extends beyond simple curiosity. Games like Baldur's Gate 3, The Witcher 3, and Dishonored create what researchers call "moral laboratories"—spaces where the consequences of choices can be observed, analyzed, and understood without causing actual harm. When you betray a companion in BG3, you're not actually hurting anyone. You're exploring a narrative branch, examining emotional responses, and understanding cause and effect in a controlled environment.

The Concept of Moral Vacation

The term "moral vacation" was coined by philosopher Thomas Hurka to describe temporary departures from our ethical frameworks in contexts where real harm is impossible. In gaming, this concept takes on particular significance. Unlike other forms of media where we passively observe moral transgressions, games require active participation. We don't just watch the villain—we become the villain, making choices and experiencing their consequences firsthand.

"The beauty of moral choice systems in games is that they allow us to ask 'what if' without the burden of 'what now.' We can explore the darkest corners of human decision-making and then simply reload a save file."

— Dr. Marcus Webb, Behavioral Gaming Research Lab

This vacation isn't escapism in the traditional sense. It's more akin to a thought experiment made interactive. When you choose to side with the Dark Brotherhood in Skyrim or embrace your vampiric nature in Vampire: The Masquerade, you're not indulging dark desires—you're conducting psychological research on yourself. You're asking: "How would I rationalize these choices? What would it feel like to prioritize power over compassion? Where are the boundaries of my empathy?"

The vacation metaphor is particularly apt because, like a real vacation, players eventually return home. The vast majority of players who complete evil playthroughs report feeling uncomfortable with their choices and often immediately start a "redemption" playthrough where they correct their previous decisions. This pattern suggests that the dark path serves not as wish fulfillment but as contrast—a way to appreciate and understand their actual values by temporarily abandoning them.

Shadow Self Exploration in Digital Spaces

Carl Jung's concept of the shadow self—the unconscious aspects of personality that the conscious ego doesn't identify with—provides a compelling framework for understanding villainous playthroughs. Jung argued that integrating the shadow, acknowledging and understanding these hidden aspects, is crucial for psychological wholeness. Games offer a unique opportunity for this integration without the risks associated with real-world shadow exploration.

When you play as a ruthless crime lord in Grand Theft Auto or a manipulative politician in Crusader Kings III, you're not expressing repressed desires. You're examining them. You're holding them up to the light, turning them over, understanding their logic and appeal. This process of examination is fundamentally different from enactment. It's the difference between studying a weapon and using one.

The gaming community has developed its own language around this phenomenon. Players speak of "getting it out of their system" or "seeing what happens" when they choose dark paths. These phrases reveal an understanding that the experience is temporary and exploratory. The evil playthrough isn't a destination—it's a journey of self-discovery, a way to map the territories of human behavior that remain theoretical in everyday life.

What makes this exploration particularly valuable is the emotional feedback games provide. When you betray a loyal companion in Mass Effect or sacrifice innocents in The Witcher, the game doesn't just show you the consequences—it makes you feel them. The companion's hurt, the weight of your decision, the way other characters react—all of this creates an emotional education that pure thought experiments cannot provide. You learn not just what it means to make dark choices, but how it feels, and often, how uncomfortable that feeling is.

The Safe Space of Consequence-Free Exploration

The phrase "consequence-free" requires careful unpacking. Games with moral choice systems are anything but consequence-free within their narrative frameworks. Choose the dark path in Dishonored, and you'll face a darker world, more enemies, and a bleaker ending. Betray your companions in Dragon Age, and they'll leave or turn against you. The consequences are real within the game's context—they're just not real in the sense that matters for actual ethics.

This distinction is crucial. The consequences in games are real enough to create emotional weight and teach lessons about cause and effect, but not real enough to cause actual harm. It's a perfect middle ground for moral exploration. You can learn that betrayal leads to isolation, that cruelty breeds resentment, that power without compassion creates enemies—all without actually betraying, hurting, or dominating anyone.

Game developers have become increasingly sophisticated in creating these safe spaces for moral exploration. Baldur's Gate 3, for instance, doesn't just present binary good/evil choices. It creates complex scenarios where the "right" answer isn't clear, where every option has costs, where you must weigh competing values. This complexity mirrors real-world ethical dilemmas while maintaining the safety of the virtual space.

The save/load mechanic adds another layer to this safe space. Unlike real life, where choices are permanent, games allow you to explore multiple paths, to see what happens if you choose differently. This ability to rewind and replay transforms moral choices from irreversible commitments into experimental variables. You can be the hero in one timeline and the villain in another, comparing and contrasting, learning from both experiences without being defined by either.

The Psychology of Player-Character Separation

One of the most fascinating aspects of villainous playthroughs is how players maintain psychological distance from their characters' actions. This separation isn't denial or compartmentalization—it's a sophisticated form of perspective-taking. Players understand that they are not their characters, that the choices they make in-game are explorations rather than expressions of their true selves.

Research by Dr. Emily Rodriguez at the Interactive Media Lab found that players use specific linguistic markers when discussing evil playthroughs. They say "my character did this" rather than "I did this." They refer to their avatar in the third person, creating grammatical distance that reflects psychological distance. This linguistic separation allows players to explore dark choices while maintaining their real-world identity and values.

This separation is healthy and necessary. It's what allows the moral vacation to function as exploration rather than expression. Players who struggle to maintain this separation—who feel genuine guilt or distress about in-game choices—often avoid evil playthroughs entirely. The ability to separate player from character, to understand the difference between exploring a perspective and adopting it, is what makes dark playthroughs psychologically valuable rather than concerning.

Common Motivations for Evil Playthroughs

- Narrative Completionism: Wanting to see all story branches and endings

- Psychological Curiosity: Understanding different moral perspectives

- Mechanical Exploration: Testing different gameplay systems and abilities

- Contrast Seeking: Appreciating the heroic path by experiencing its opposite

- Safe Transgression: Experiencing forbidden choices without real consequences

Interestingly, players often report that evil playthroughs strengthen their real-world values rather than undermining them. By experiencing the emotional weight of dark choices, by seeing how betrayal feels even in a fictional context, players develop a deeper appreciation for trust, loyalty, and compassion. The dark path, paradoxically, illuminates the value of the light.

Games as Moral Philosophy Laboratories

Philosophy professors have begun using games like Fallout and Mass Effect in their ethics courses, recognizing that these games present moral dilemmas with a complexity and emotional weight that traditional thought experiments lack. The trolley problem becomes more than an abstract puzzle when you're the one standing at the switch, when the people on the tracks have names and stories, when you have to live with your choice for the rest of the game.

Games excel at presenting what philosophers call "moral luck"—situations where the rightness or wrongness of an action depends on factors beyond the actor's control. In The Witcher 3, you might make a choice that seems reasonable at the time, only to discover hours later that it led to tragedy. This delayed consequence system mirrors real life more accurately than most moral philosophy examples, where outcomes are immediate and clear.

The laboratory metaphor is particularly apt because games allow for repeated experimentation. You can make one choice, observe the results, reload, and make a different choice. This ability to test moral hypotheses, to see how different ethical frameworks play out in practice, provides a form of moral education that's both engaging and effective. You're not just learning about utilitarianism or deontological ethics—you're experiencing them, seeing their strengths and limitations in action.

Moreover, games often present moral dilemmas that don't have clear right answers. Should you sacrifice one person to save many? Is it acceptable to lie to prevent greater harm? Can the ends ever justify the means? These questions have occupied philosophers for millennia, and games allow players to grapple with them in contexts that feel immediate and personal. The answers you discover through gameplay may not be definitive, but the process of seeking them is invaluable.

The Redemption Arc: Returning from the Dark Side

Perhaps the most telling aspect of evil playthroughs is what happens after them. The overwhelming majority of players who complete a villainous run report feeling a strong desire to "make things right" through a subsequent heroic playthrough. This pattern reveals that the dark path serves not as an end in itself but as a means to understanding—a journey that makes the return home more meaningful.

Players describe their redemption playthroughs with language that suggests genuine emotional investment. They talk about "apologizing" to companions they betrayed in previous runs, about "doing better this time," about the relief of making choices that align with their actual values. This emotional response indicates that the evil playthrough created a form of moral contrast that deepened their appreciation for ethical behavior.

The redemption arc also reveals something important about human psychology: we learn as much from our mistakes as from our successes, perhaps more. By experiencing the consequences of dark choices, even in a virtual context, players develop a more nuanced understanding of why certain behaviors are harmful. The lesson isn't abstract—it's felt, experienced, remembered.

Some players report that their evil playthroughs made them more empathetic in real life. By understanding how easy it is to rationalize harmful choices, how slippery the slope can be, they became more aware of their own potential for moral compromise. This awareness, paradoxically gained through virtual villainy, made them more vigilant about their real-world ethical decisions. The dark path, in this sense, served as a vaccine—a controlled exposure that strengthened their moral immune system.

The Future of Moral Choice Systems

As games become more sophisticated, so too do their moral choice systems. Modern RPGs are moving away from simple good/evil binaries toward more nuanced representations of ethical complexity. Games like Disco Elysium and The Forgotten City present moral dilemmas where every choice has costs, where there are no purely good options, only different shades of compromise.

This evolution reflects a growing understanding among developers that moral choice systems serve a purpose beyond simple player agency. They're tools for psychological exploration, for moral education, for understanding the human condition. The best moral choice systems don't judge players—they challenge them, make them think, force them to confront the complexity of ethical decision-making.

Emerging technologies like AI-driven NPCs and procedural narrative generation promise to make moral choice systems even more sophisticated. Imagine games where characters remember not just your major choices but your minor ones, where your reputation is built from hundreds of small decisions rather than a few big ones. These systems could create moral laboratories of unprecedented complexity, spaces where players can explore the cumulative effects of their choices over time.

The future may also bring more explicit integration of psychological research into game design. Developers are increasingly consulting with psychologists and ethicists to create choice systems that are not just engaging but educational, that help players develop moral reasoning skills and emotional intelligence. The line between entertainment and education is blurring, and moral choice systems are at the forefront of this convergence.

"The most valuable thing games teach us isn't how to be heroes—it's how to understand why people become villains. That understanding, that empathy for the path not taken, makes us better people in the real world."

— Jennifer Park, Narrative Designer, Obsidian Entertainment

Conclusion: The Value of Virtual Villainy

The phenomenon of good people playing evil characters isn't a paradox—it's a feature, not a bug, of human psychology. Our capacity for moral imagination, for understanding perspectives different from our own, is one of our most valuable traits. Games that allow us to explore dark paths safely are exercising this capacity, strengthening our ability to understand, predict, and ultimately resist harmful behaviors in real life.

When we choose the dark path in a game, we're not revealing hidden desires or moral weakness. We're conducting research, exploring possibilities, testing boundaries. We're asking important questions about human nature, about the circumstances that lead to harmful choices, about the difference between understanding evil and endorsing it. These are questions worth asking, and games provide a uniquely safe and engaging space to ask them.

The moral vacation that games provide isn't escapism—it's exploration. It's a journey into the shadow self that makes us more whole, more understanding, more aware of our own capacity for both good and evil. By experiencing the consequences of dark choices in a virtual space, we develop a deeper appreciation for ethical behavior in the real world. We learn not just what we should do, but why we should do it, and that understanding is far more valuable than simple rule-following.

As games continue to evolve, as moral choice systems become more sophisticated and nuanced, their potential as tools for psychological growth and moral education will only increase. The future of gaming isn't just about better graphics or more immersive worlds—it's about creating spaces where players can safely explore the full spectrum of human behavior, learning from both their virtual triumphs and their virtual failures.

So the next time you find yourself choosing the dark path in a game, don't feel guilty. You're not indulging your worst impulses—you're exploring them, understanding them, and ultimately, learning to resist them. You're taking a moral vacation that will make you a better person when you return home. And that's not just good gaming—it's good psychology.